The other night I did the most thrilling thing a grown adult can do: I changed a lightbulb.

It was one of those “lasts 15 years!” LEDs. You know the ones. I screwed it in, basked in the smug glow of modern engineering… and then remembered I bought the exact same “15-year” bulb about two years ago.

At which point my brain did that annoying thing where it refuses to let you enjoy your own kitchen until you have personally investigated the entire economic system.

The conspiracy bit (and yes, it is real)

Picture this: a private room. Heavy furniture. Serious men in serious suits. Not twirling moustaches, just shuffling papers like they are auditioning for Accountants: The Musical.

They are the big lightbulb manufacturers of the day, gathering under the banner of something called the Phoebus cartel. The details vary depending on which archive you read, and no, we do not have a cosy little transcript of their banter. But we do have the outcomes, and they are the point.

The plan, in essence, is brutally simple. If bulbs last too long, people stop buying bulbs. If people stop buying bulbs, the numbers stop going up. And if the numbers stop going up… well, that is how executives get that haunted look in their eyes.

So they do what clever people do when they want to make a bad idea feel respectable. They make it a standard. A target. A rule. 1,000 hours. Not “at least”. Not “aim for”. Just “this is the lifespan now”.

Then they build the bureaucracy to enforce it. Tests. Monitoring. “Life reports”. Fines for any manufacturer whose bulbs had the audacity to keep glowing beyond the agreed limit.

And suddenly, durability is no longer a triumph of engineering. It is a compliance issue.

I learnt of all of this from a documentary

The Lightbulb Conspiracy traces how manufacturers learned that making things last forever is brilliant engineering… and terrible for quarterly growth.

What we learn (and what is actually going on)

1) Planned obsolescence is not a conspiracy theory. It is a business strategy.

The documentary’s central idea is that a lot of modern products do not “wear out” so much as they are politely escorted towards an early grave. Sometimes this is physical. Sometimes it is psychological. Often it is both.

2) There are two kinds of “obsolete”.

Technical obsolescence is when something breaks, often in a very specific, predictable way. Psychological obsolescence is when it still works, but you are made to feel like it should not. Modern marketing is basically: “your stuff is embarrassing, darling”.

3) The bin is not the end of the story.

When we replace things early, the waste does not evaporate. It gets shipped, dumped, burned, dismantled. The cost is paid somewhere else, often by people who did not get a vote in the “let us make this slightly flimsier” meeting.

The most shocking findings (the bits that make you mutter into your tea)

1) A lifespan cap was treated like a success. In the Phoebus era, the bulb was one of the first mass consumer products where longevity became a problem to be solved, not a feature to be celebrated.

2) The “Centennial Bulb” is still burning. In Livermore, California, there is a lightbulb that has been glowing since 1901. The film points out the delicious irony that it has outlasted multiple cameras installed to film it. It is a perfect symbol of what is technically possible when longevity is the goal.

3) Someone seriously proposed compulsory expiry dates for products. During the Great Depression, Bernard London argued for giving products an official “lease of life”, after which they would be considered legally dead and handed over to be destroyed. It is both horrifying and weirdly honest, which is the worst combination.

4) Printers are basically the Disney villains of consumer goods. The documentary looks at printer service manuals and points to lifespan limits set by design, sometimes enforced via internal chips. Not “it broke”. More “it has decided it has done enough living now”.

5) Even the “good old days” of innovation had a dark little twist. There is a story about early nylon stockings being so durable that they caused a problem. The problem was not “how marvellous, we have reduced waste”. The problem was “hang on, if they last too long, we sell fewer”. So the stockings were engineered to be more fragile. Imagine being paid to invent a miracle, then being paid again to un-invent it.

What is happening today (the hopeful bit, plus the “we are not done yet” bit)

Repair is becoming policy, not a hobby. In the EU, new rules are pushing repair as the default, including obligations around offering repairs and discouraging tactics that block them. This is slow, unglamorous work, but it is the kind that actually changes markets.

Phones are being dragged, blinking, towards durability. The EU has also been rolling out requirements around smartphones and tablets that make durability and repairability harder to hide, including expectations around spare parts and battery performance.

France is pushing ahead with durability scoring. France has been experimenting with repairability scores for years, and is now expanding towards a broader durability index for certain appliances. It is not perfect, but it shifts the question from “how shiny is it” to “how long will it live”. Which is progress.

The UK has steps, but not the whole staircase. The UK has repairability measures for some household appliances, but coverage is patchier than most people assume, especially for the tech that causes the most grief.

And LEDs? LEDs can genuinely last a long time, but “life” is often measured as “how long until it gets noticeably dimmer”, not “how long until it definitely will not die”. Heat management and the little electronics inside (drivers) can be the weak link, especially in cheap bulbs or enclosed fittings.

Top 5 things we can do about it (without moving to a cave)

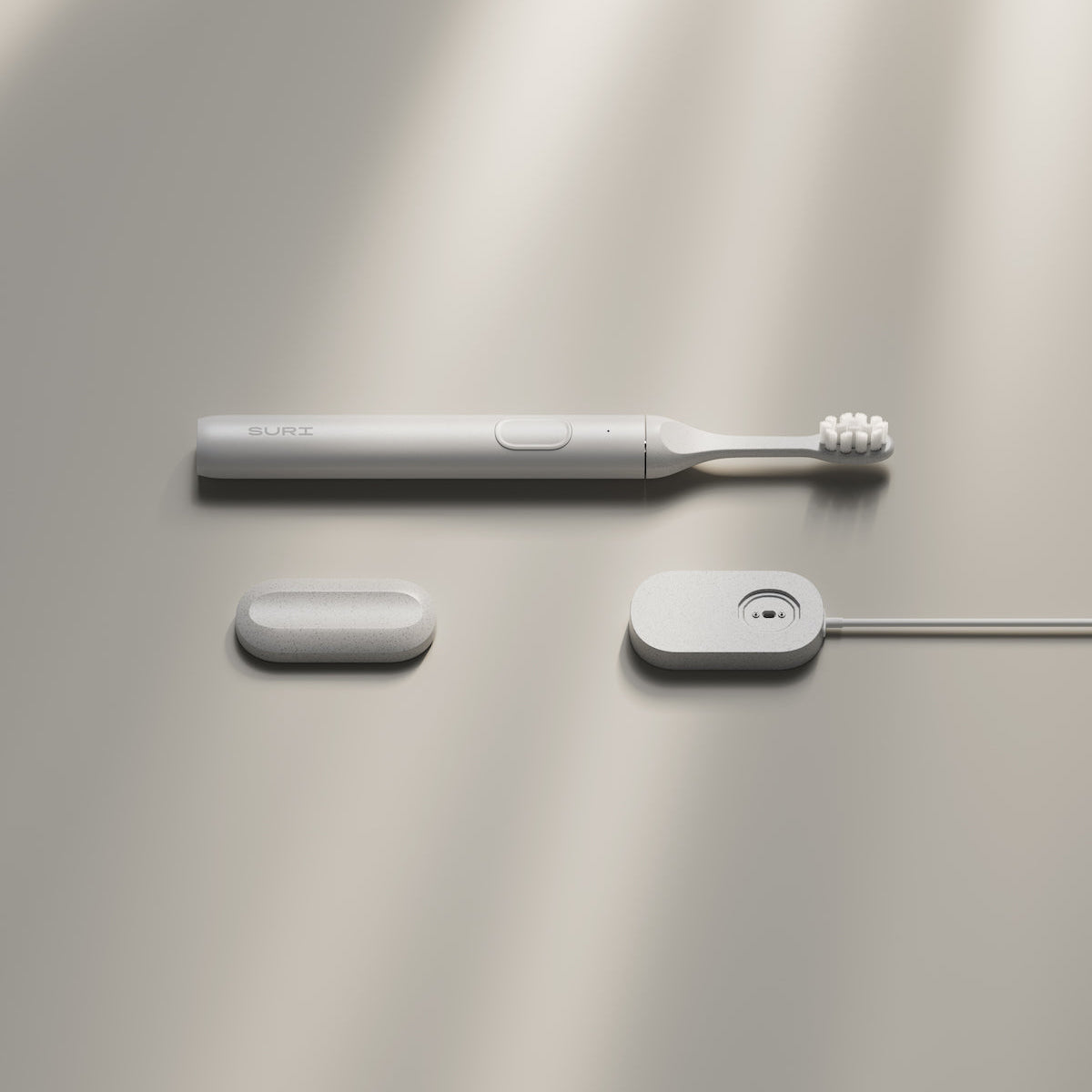

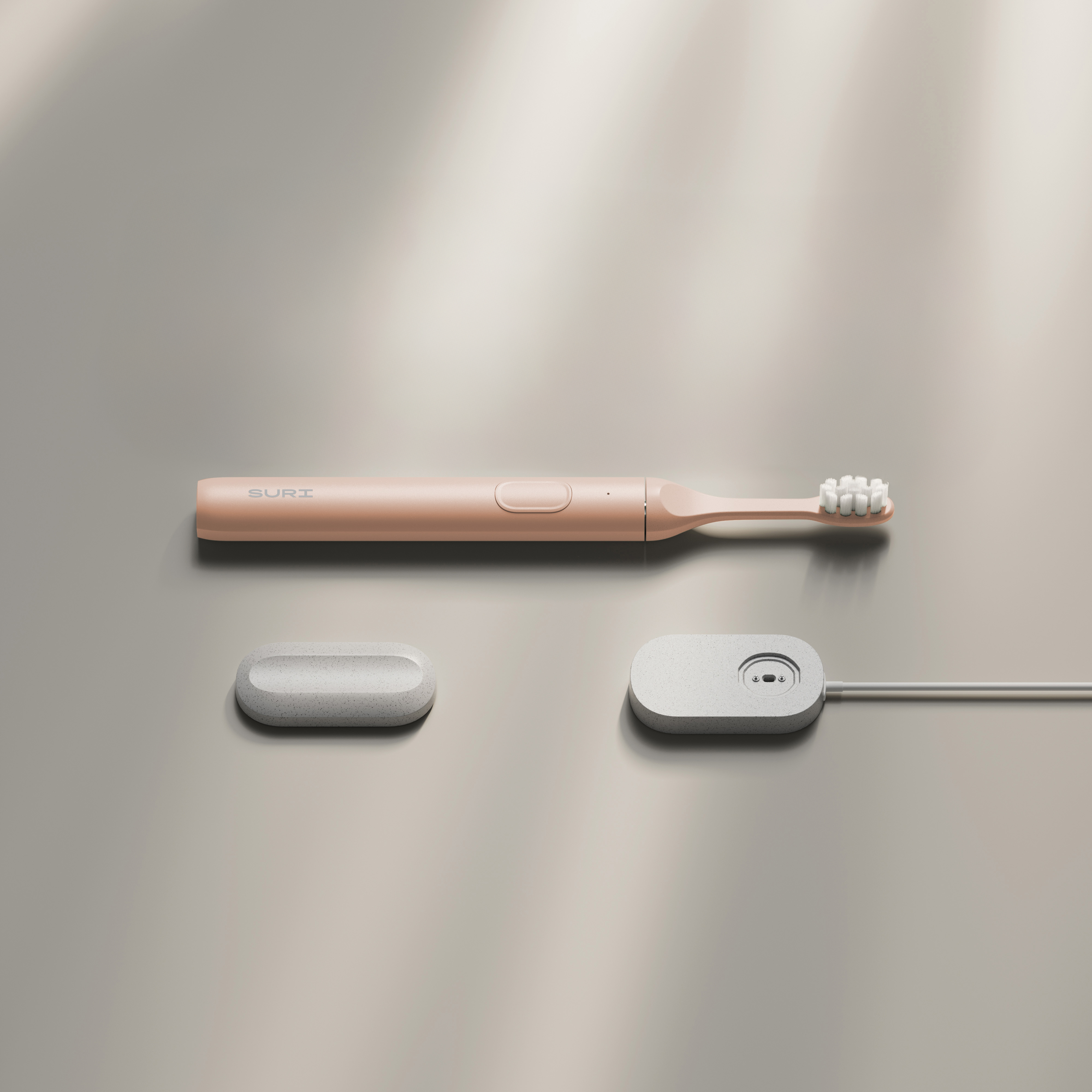

1) Treat the warranty as a truth serum. Ignore the “lasts 15 years!” headline and look at the warranty. If a brand truly believes in longevity, it will back it up. Bonus points if you can actually find the warranty terms without needing a machete and a law degree.

2) Buy for repair, not just replacement. For lighting, prefer fixtures with replaceable bulbs rather than sealed, integrated LED units. If you do buy integrated LED fittings, look for those designed with replaceable components. You want “I can fix this” energy, not “well, the whole ceiling is landfill now”.

3) Do not let software quietly shorten your product’s life. If a firmware update can change whether something works with third-party parts, you are not fully owning the thing. You are renting it with extra steps. Turn off automatic updates when you can, especially on printers, and look up what an update actually does before installing it.

4) Make early failure expensive for the brand. If something dies suspiciously early, do not just sigh and reorder. Claim under warranty. Use your consumer rights. Escalate. Leave reviews that mention durability and repair. Brands hate two things: sunlight and data.

5) Support the boring policy stuff, because it is secretly the most powerful. Right to repair laws, durability labels, spare parts requirements, design standards. These are the levers that make “long-lasting” normal rather than niche. If you want a world where durability wins, this is how you rig the game in our favour for once.

The punchline (and the point)

The documentary might be from 2012, but the core message still lands: we are living inside an economy that rewards products for dying.

But the tide is shifting. Repair is being legislated. Durability is being labelled. Manufacturers are being nudged, shoved, and occasionally dragged towards responsibility.

Which means we get to do the most satisfying thing of all: outsmart the system.

Start small. Choose one category in your life where you stop buying “disposable by default”. Lightbulbs are a wonderfully petty place to begin.

Because if a light can burn for a century, the least we can do is stop paying extra for darkness.